ddddMinimal jeune fille

Minimal Jeune Fille

“I want people to be beautiful”

The Young-Girl is the spitting image of the total and sovereign consumer; and that’s how she behaves in all realms of existence.

The Young-Girl knows the value of things ever so well. Often, before decomposing too visibly, the Young-Girl gets married.

The Young-Girl is good for nothing but consuming; leisure or work, it makes no difference. Because of its having been put on a level of equivalence with all intimacy in general, the Young-Girl’s intimacy has become something anonymous, exterior, and object like.

The Young-Girl never creates anything; she recreates herself. 1

The film Safe (1995) directed by Todd Haynes gave us Julianne Moore playing the role of housewife Carol White; a painfully brilliant Moore spirals out of control, physically and mentally, as her character is diagnosed with “multiple chemical sensitivity” – visibly falling apart, as her body reacts in an extreme way to the toxins and products experienced and used in everyday life of the 1980s. As her condition increasingly worsens, she moves into a new age retreat, in the hope of finding safety from the chemical and industrial world and relief from her symptoms and the anxiety these cause. This ‘allergy’ is not only the physical manifestation of this woman’s psychological reaction to the packaged, wipe-clean, consumable world of the late twentieth century, but also an analogy for her emotional (non)existence and inherent paranoia in her relationship to the outside world.

Artist Juliette Bonneviot created the character Jeune Fille Minimale, as a protagonist to inspire a new body of sculpture and video, exploring what writer Timothy Morton describes as a “dark ecology”, akin to a noir film, in his book The Ecological Thought. Yet unlike Moore’s character, Bonneviot’s Jeune Fille is not afraid of what the world will do to her, but instead, develops a neurosis about what her conspicuous consumption and lifestyle will do to the world. However, the anxiety of how we live and consume today is palpable in both characters experiences and their main relationship is not with another person, but with the stuff in the world around them. Bonneviot also likens her character to the figure of The Young-Girl, in the French philosophical collective Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young- Girl, as she is the perfect Young-Girl, a networked body, consuming the consumable, shaping herself and her life, thus becoming the ultimate consumable herself.

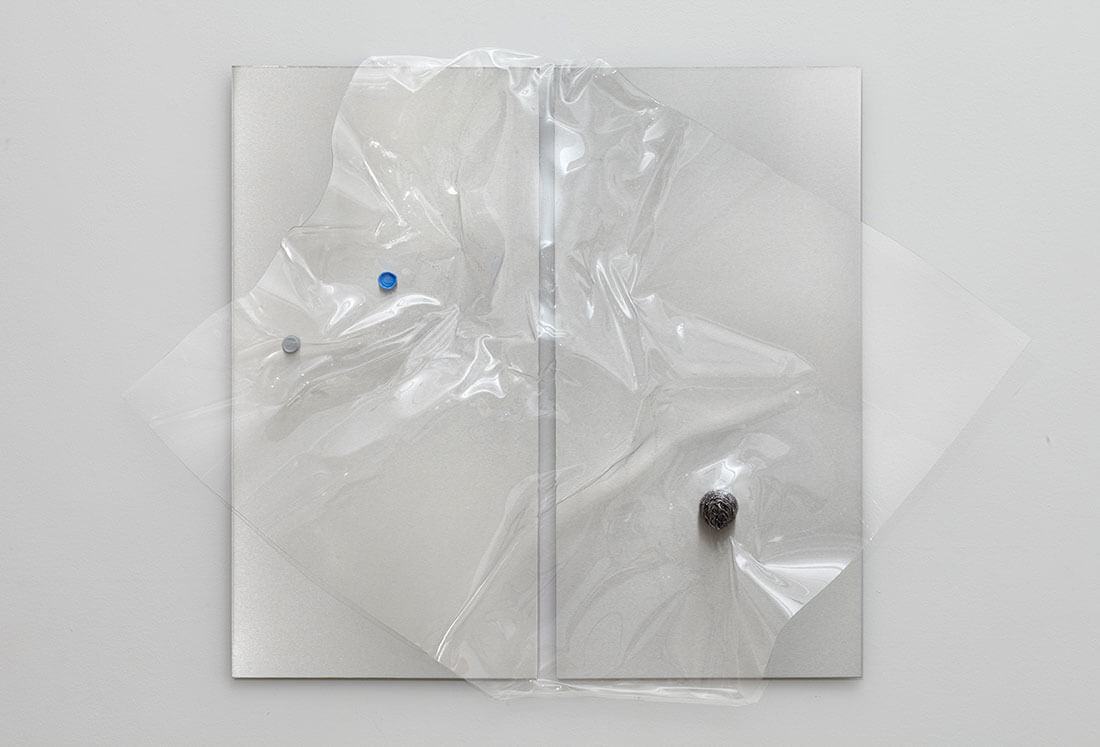

Bonneviot’s antagonist is waste, in particular plastic waste. Plastic is a material that is associated with wipe-clean sanitation and also a protective barrier for foods and other goods, to ensure their ‘purity’ for the consumer, regardless of how dirty or covered in insecticides or factory residue they actually are. Plastic is safe (incidentally, Moore’s character zips herself up to hide from the world in a plastic tent in Safe) and can keep things clean and fresh. Bonneviot’s Jeune Fille is presented alongside the objects she uses, in sculptural forms, depicted in videos washing, wiping, shaving, and perfecting the presentation of her own objecthood. Alongside these, the objects are displayed as if museum pieces, or relics, from life today (chosen because they are not disposable) – laid out as if an anthropological display, for us to interpret their use and role, and covered by sheets of plastic to either keep the objects sanitary, or the audience safe from the unsanitary used items. This heightens their uncanny and abject nature. Alongside these are the PET Woman sculptures; torsos of female bodies molded from the same wrinkly plastic sheeting, as if protective layers for Renaissance casts, with transcribed texts from forums on the internet discussing waste.

The places where things are made from plastic are often the most unsanitary places that we inhabit. Toilets, sanitary product disposal bins, showers, wrapped and cling filmed meats, fish and vegetables… they also often involve the body – either to consume, or to clean, or to protect. Plastic, a substance far from our mortal flesh in its composition, that will not often degrade biologically, is the thing that we choose to keep us safe. Like the Young-Girl, this is also a symptom and product of late-Capitalism. Akin to the way the Young-Girl’s body and beauty is produced by consuming; products clean, buff, shape, remove hair, skin and nails, altering and disinfecting it from its messy human excesses. Fluid, discharge, blood, saliva, spit, shit, urine and semen are all products to be collected, wiped clean and eliminated by our plastic friends.

Artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles made the work Touch Sanitation between 1977 and 1980 in a New York sanitation centre. Ukeles stated: ‘“I’m not here to watch you, to study you, to analyze you, to judge you. I’m here to be with you: all the shifts, all the seasons, to walk out the whole City with you.” I face each worker, shake hands, and say: “Thank you for keeping NYC alive.”’ This performance took place every day and involved 8,500 sanitation workers – Ukeles has explained she was not there to “help” the workers but to be part of the daily routine, to be a part of their network, in order to keep them “alive”. Ukeles wrote the text Manifesto for Maintenance Art in 1969, just after the birth of her first child, in order to create a position for herself in which she could be a mother and artist, making work within the structure and action of everyday life, stating: “I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc.,” it reads. “Also, up to now separately I ‘do’ Art. Now, I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art.” Bonneviot has expressed an interest in Ukeles and her approach and stance to work and life. However, in contrast to Ukeles more Utopian outlook (in that it does not necessarily seem critical of the system, or an attempt to undermine it, rather to state that art cannot be totally dissociated from life, and that one must inform the other) Bonneviot’s seems more sharply critical of the way we live now. It also could be described as a kind of end-point to what Alan Kaprow described as the “merging of art and life”; where the reality of life is mirrored and performed, where humans are subject to infinite simulacrum, consuming in order to perform and transform their own object-hood. In turn enabling them to then be consumed by others, in an endless Mobius strip of spectacle.

Kathy Noble

1 Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, Tiqqun, 1999

ddddShanghai Gesture

Shanghai Gesture 2 @ Wilkinson Gallery

In The Record of the Classification of Old Painters, sixth century Chinese art historian Xie He established the ‘six principles of painting,’ classing artists into six categories. The first was ‘Spiritual Resonance,’ while the final was ‘Transmission by Copying.’ These two poles, and what lay between, hence emerged as a critical factor in both the creation and appreciation of Chinese painting.

‘Transmission by Copying’ refers simultaneously to the circulation of the original as well as a comprehension of the fundamental method of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Xie believed that there was no creativity involved in this category; thus, he demoted it to the sixth and final ranking. However, for those new to the art of painting and calligraphy, it represents the inception of a long journey towards the peak of the pyramid.

Juliette Bonneviot’s ‘gesture’ can be seen as an instance of ‘Transmission by Copying,’ even though she has never taken the ten-plus-hour-long flight to the other side of the world, nor has she heard of Xie He. Her ‘original’ is the Chinese version of the poster of a Hollywood film. The scroll wiggles down from what resembles a ‘typically Oriental’ aluminum arch with clumsy characters, which, strangely enough, are written in the ancient Chinese style of seal script. The red circles and crosses, denoting right and wrong, are copied from Gu Wenda’s Mythos of Lost Dynasties, a pseudo-character series that pointedly expresses appreciation and disapproval. Bonneviot’s writing thus echoes a style of calligraphy that is more than two thousand years old, filtered through the revised ‘copy’ of a contemporary Chinese artist-calligrapher very much steeped in his culture’s aesthetic tradition. And, while Bonneviot is not endeavoring to attain the ‘Spiritual Resonance’ that Xie claimed as the goal for all painting, she instead achieves an intriguing scrutiny of a series of simplified symbols. This unites Bonneviot with the massive degree of ‘Transmission by Copying’ currently taking place in China. The copycatting gadgets imitate not only the appearance but also the brand name of major Western products, revealing the Chinese public’s image of the contemporary lifestyle of luxury – one of the more extreme examples of Bourdieu’s ‘symbolic capital.’ This unprecedented process is also scrutinized by Bonneviot in her ‘gesture,’ wherein mass production is captured through ironic symbols: the sweet ‘candy bar’-shaped music player hanging helplessly alongside the silk and ink. The brand of the player, iRiver, easily recalls the fame of iPod. But, upon further scrutiny, it turns out to be a South Korean product. And so what? It is as far as forever, seven time zones away, and China and Korea are so close to each other. From here, even I can barely see any difference.

Nevertheless, the soundtrack in those players brings another kind of ‘Spirit’ to the ‘Copying.’ The sound of Chinese instruments and electronic drums showcase a blend of acid rock fused with the exotic. This soundtrack also draws the outline of a comfort zone. It’s mute and undisturbed inside, protected by the boundary of distance and language, and noisy and chaotic outside, stuffed with a nod towards the African continent as well as absurd poetic monologues.

I have a snow globe in my hands, and there’s a tiny little double-roof pavilion inside, as well as a little oriental man in a white garment, standing on one leg, arms held up and balanced on his sides. It is not snow that covers the tiny little ground, but yellow leaves. I shake the globe. From its base, the sound of a bamboo flute being played, while the leaves waving up and falling gradually around the little man reveal and then re-cover the black character written on the red background. I am guessing it reads ‘lucky.’ I stare at the globe. It is China. Almost.

Li Qi

ddddPet Women

Photography by Hans-Georg Gaul

PET plastic sheet ♳ 60 x 48 x 26 cm

Photography by Hans-Georg Gaul

PET plastic sheet ♳ 60 x 48 x 26 cm

Photography by Hans-Georg Gaul

ddddXenoestrogens

Installation view in Inflected Objects # 2 Circulation – Otherwise, Unhinged, curated by Melanie Bühler, Future Gallery

Installation view in Safe to drink, Museum Kurhaus Kleve

Installation view in Crash Test, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, MO.CO. Montpellier Contemporain.

(Foreground: Phillip Zach Seeing Red II (hugger), 2018)

Xenoestrogens

In her new series Xenoestrogens, Juliette Bonneviot continues her investigations into the nexus between ecology and gender by engaging with the materiality of things through a focused practice. She makes a speculative exploration of the hidden life and power of the chemical compound xenoestrogen (meaning: foreign estrogen), which looks like and mimics estrogen (or oestrogen).

The exhibition consists of paintings Bonneviot made using her collection of different compounds containing types of xenoestrogens. She begins with the core – the chemical xenoestrogen as a material – and spirals outward into many of its biological, cultural and philosophical implications.

In Bonneviot’s thinking, matter is powerful, active and alive. It is dispersive and it moves constantly. Xenoestrogens are a perfectly concentrated example of this movement. Many are deeply disruptive to living systems, having been linked to birth defects, cancerous growth, hormonal disruption, and abnormalities in animal and human reproductive health.

Xenoestrogens can be organic, or synthetic, or mineral. Synthetic xenoestrogens are perhaps the most infamous, found in birth control pills, silicones, oils and lacquers, coolants and insulating fluids, BPA and pesticides, detergents and plasticizers, linens, lotions, shampoos, beverage cans and lacquers. Organic xenoestrogens are found in plant, animal and human life, often performing valuable biological functions, like curbing population growth.

Bonneviot’s process is studied; she gathers, catalogs, archives and arranges her compounds meticulously. In the process of collecting, Bonneviot drew on philosopher Jane Bennett’s description of hoarding as an intentional kind of work, emerging from one’s own attuned orientation to thing-life.

For these paintings, Bonneviot used a variety of xenoestrogens, including: metalloestrogens, which predate oestrogens (and are sourced from aluminum, lead, copper, chrome, antimony, cadmium); phytoestrogens from plants, (extracted from soy and sesame seeds and flax plants); mycoestrogens (pulled from zearalenone, a fungi in grains); and other artificial xenoestrogens (siphoned from silicone, phthalates, BPA, epoxy resins, additives, aspirin and of course, the pill).

The paintings’ minimalism belies their procedural complexity. They involved experimentation with both traditional and unorthodox materials to find the right range of colors, and the right pairings of surfaces with binders. Her mixtures reveal vivid, saturated pigment groups: reds, yellows, blues, earth-colors and greys. (Red, for example, is sourced from silicone rubber, copper, the cadmium pigments in architectural paints and E127 Erythrosine B, a food coloring).

Testing their resistance and flexibility as mediums, she created a linen fabric support with wood floor lacquers to bind, a support of epoxy resins to bind atop PVC, and, in a final iteration, silicone as both binder and surface.

Natural and industrial production intersect on the canvas; the synthetic is mixed in with mineral and organic. Easy binaries and divisions are muddied, as a result. In this flow from ancient organic compounds into the modern and artificial, the viewer is forced to consider a wide arc of time – from the pre-mammalian era, to the future, in which our offspring will be shaped by chemical actants loose in the world now.

In sourcing these xenohormones from a range of organic and synthetic sources, Bonneviot gestures strongly at the “interstitial field of non-personal, ahuman forces, flows, tendencies and trajectories” that define life, as Bennett writes in her seminal text, Vibrant Matter. The materiality and artistry of xenohormones as they both impress and express is one aspect of Bennett’s “agency of assemblages,” or the “working whole made up, variously, of somatic, technological, cultural, and atmospheric elements.”

We’re asked to consider the world from the perspective of the chemical itself – where it was birthed, where it journeyed, and in what form it entered the bloodstream, the water and the technological environment. We are also asked to think on environmental contamination, as volatile xenoestrogens lurk, resilient, in treatment plant runoff and pesticides and waste, eroding hormonal and ecological balance.

Chemicals are always present before us as actants, though not always detectable to the naked eye. They transform our human and animal bodies into spaces of great drama. We’re just a few of many assemblages being wrought and remade in a newly synthetic world.

Nora N. Khan

Photography Mark Blower

Photography Hans-Georg Gaul.

Photography by Hans-Georg Gaul

ddddCV

Born 1983 in Paris, lives and works in Paris

juliette dot bonneviot (at) gmail dot com

2002-2008 MFA – Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris (DNSAP)

↓ Press review

Solo and two persons exhibitions

2015

Xenoestrogens, Autocenter, Berlin

2014

Minimal Jeune Fille, Wilkinson Gallery, London

2012

Last Spring/Summer, Juliette Bonneviot and Aude Pariset, Les Urbaines, Lausanne

Shanghai Gesture 2, Wilkinson Gallery, London

Pumping Dancers, CEO, Malmö

2011

Pink Pink Stink Nice Drink, Circus, Berlin

Shanghai Gesture, Mark & Kyoko, Berlin

2010

Succubus, Juliette Bonneviot & Aude Pariset, PMgalerie, Berlin

Selected group exhibitions

2022

Elephant’s leg, Tonus, Paris

2020

Your friends and neighbors, High Art, Paris

2018

Crash Test, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, MO.CO. Montpellier Contemporain, Montpellier

Polymeric lust, Display, Berlin

Body echo, NıCOLETTı, Paris

2017

Le Rêve des Formes, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Safe to drink, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Kleve

(Dys)-tropism, Super Dakota, Brussels

2016

Inflected Objects # 2 Circulation – Otherwise, Unhinged, Future Gallery, Berlin

Abstract Sex, CCS, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson

Me, Inc., Rotwand – Sabina Kohler & Bettina Meier-Bickel, Zurich

The Green Ray, curated by Andrew Hunt, Wilkinson Gallery, London

When The Cat’s Away, Abstraction, Anna Jill Lupertz Gallery, Berlin

Sophia’s Potluck, hotel-art.us, Berlin

Young Girl Reading Group Show, curated by Julia Moritz & YGRG, ArtGenève, Geneva

2015

Co-Workers, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris

Looks, ICA, London

Percussive Hunter, Akbank Sanat, Istanbul

„Whatever man built could be taken apart”: Image / Order, NAK, Wiesbaden

Mankind/machinekind, Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna

The Vacancy, Galerie Crone, Berlin

New Needs, curated by Rosa Rendl and Isabella Ritter, Pavilion curated by HHDM, Haus Wittman, Etsdorf am Kamp, Austria

X is Y, Sandy Brown, Berlin

Les Oracles, curated by Marisa Olson, XPO Gallery, Paris

IMMUNITY (chorus), Vault, Berlin

Curatron #4, Platform Stockholm, Stockholm

2014

nature after nature, Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel

Art Post-Internet, curated by Karen Archey and Robin Peckham, UCCA, Beijing

Uplifting of Destruction, curated by Eloïse Bonneviot and Anne de Boer, Jupiter Woods, London

Plastic Age, Faszination und Schrecken eines Materials in Kunst und Wissenschaft, Eres Foundation, Munich

Call Me On Sunday, Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna

High Lure Image Content, co-curated by Julie Grosche and Sara Knox Hunter, ΚΘΦ, Richmond

BASIC ZONE, curated by Alessandro Bava, Casamadre Arte Contemporeana, Naples

Nostalgia, Glasgow International, Glasgow

Fight, Center, Berlin

Forza Minibar, Minibar Art Space, Stockholm

They Live, Shanaynay, Paris

2013

Entre-temps…, Brusquement, Et ensuite, 12e Biennale de Lyon, Lyon

Where Narrative Stops, Wilkinson gallery, London

False Optimism, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

Analogital, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Salt Lake City

Light Box 10, Project Number, London

Surface Tension, Galerie Andreas Huber, Vienna

Sallie Gardner: A Group Exhibition, Michael Thibault Gallery, Los Angeles

The Mediterranean Dog, curated by Elise Lammer, Cole, London

Yellowing of the Lunar Consciousness, Massimodeluca, Venice

How Many Eyeballs Tame Complexity, curated by Ben Vickers, BiennaleOnline

4., CEO, Malmö

After School Special, performance, Bergen Kunsthall, Bergen

Gordian Conviviality, curated by Max Schreier, Import Projects, Berlin

2012

The Dark Cube, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Very abstract and really figurative, Galerie Emanuel Layr, Vienna

entrance 1, entrance 2, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin

Can’t Touch This, curated by Karen Archey, Art Micro Patronage

2012, curated by Lindsay Jarvis, The Mews Project Space, London

July, CEO, Malmö

Business Innovations for Ubiquitous Authorship, curated by Artie Vierkant, Higher Pictures, New York

Entourage Vip Backstage, curated by Ilja Karilampi, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Züricher Bildhauer, Zurich

Bcc #7, Stadium, New York

Twothousandtwelve, CEO, Malmö

2011

Rhododendron (ii), Space, London

Based In Berlin, Monbijou Park, Berlin

Where Language Stops, Wilkinson Gallery, London

Rhododendron, W139, Amsterdam

Metrospective 1.0, Future Gallery and PROGRAM, Berlin

Amerika, América, Amérique! , presented by Mark&Kyoko, Cleopatra’s Berlin, Berlin

Venus in a shell, Fluxia, Milan

A Painting Show, Autocenter, curated by Aaron Moulton, Berlin

Land Art For A New Generation, Showroom Mama, (show and residency), Rotterdam

Travelin’ light, curated by Felisa Funes, Grimmuseum

2010

Sculpture Storage, La MaMa Gallery and Cooper Union School of Art, New-York

The Bar, Kunsthalle Athena, Athens

Dust Snow, Winter Sculpture Parc, Poznan

Almeria to Béziers to Newquay, Darsa Comfort, Zurich

BYOB, curated by Anne de Vries & Rafaël Rozendaal , Bureau Friederich projectstudio, Berlin

Distorted Viewport, curated by Spiros Hadjidjanos, Forgotten Bar, Berlin

Exhibition IV, curated by 10/2/10, Berlin

Rapidshare curated by Isaac Bigsby Trogdon, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin

Domestica II, curated by Antoni Hervas Cortes, Barcelona

Enchanted, School of Development, Berlin

Exhibition I, curated by 10/2/10 (Alex Freedman, Annice Kessler, Kathryn Politis and Claudia Rech),Kim bar, Berlin

Sculpture Storage, La MaMa Gallery curated by The Cave and The Cooper Union School of Art, New York

2009

Women Get Fucked, Alogon Gallery, Chicago Project Room, Chicago

Sally’s, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin

Das 2. Dragoner Regiment im Jahr 2009, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin

Domestica, curated by Antoni Hervas Cortes, Barcelona

2008

XYZ, Atelierhof, Berlin

Publications, catalogues

2018

Speculations on Anonymous Materials, Nature after Nature, Inhuman, Koenig Books, ISBN : 9783863357320

Crash Test – The Molecular Turn, Les Presses Du Réel, ISBN : 978-2-490123-01-8

2016

Intersubjectivity Vol. 1 Language and Misunderstanding, Abraham Adams, Lou Cantor (Eds.), Sternberg Press, ISBN 978-3-95679-199-4

Aesthetic Politics in Fashion, Elke Gaugele (Ed.), Sternberg Press, ISBN 978-3-95679-079-9

2015

Percussive Hunter, exhibition catalogue, Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2014, Akbank Sanat

XenoEstrogens (the Disappearing Male), portfolio, BOMB Magazine

Les Oracles, Marisa Olson and Claire Evans, XPO gallery, ISBN 978 2 9541349 0 1

2014

Art Post-Internet: INFORMATION/DATA by Karen Archey

Plastic Age, Eres Foundation, Munich, ISBN 978-3-00-046784-4

2013

Entre-temps…, Brusquement, Et ensuite, 12e Biennale de Lyon, ISBN : 978-2-84066-648-6

57 CELL issue #2

West Space Journal #1, West Space

2012

Wandering No.1, Wandering Magazine, ISSN: 2235-4417

Linear Manual frontcover, TLTRPreß

2011

PWR PAPER #6, PWR PAPER

Larry’s Se7en, Larry’s

2010

Dust Snow, Morava Books, ISBN: 978-83-926924-2-3

2009

Sally’s, Floating Head Publication

Selected bibliography

2018

Ingrid Luquet Gad. “Crash Test” à La Panacée : art contemporain et anthropocène, Les Inrockuptibles #1160

La jeune scène française du prix Ricard, Numéro art #3

2016

Melanie Bühler. Upcycling Zonder Ophouden, Metroplis M, Issue #4, August September

Christa Benzer. New Materialism, Springerin, Issue #1/16

2015

Chloe Stead. Plastic Surgery, Frieze d/e, Issue #21

Benoît Lamy de La Chapelle. Redefining life Post Human, twenty years later, 02

Elena Gilbert. Domestic Unrest, Sleek, Issue #44, Winter

2014

Eleanor Nairne. Juliette Bonneviot, Frieze Magazine Issue #162, April

Alessandro Bava. Basic Zone, Novembre Magazine, Issue #9, Spring/Summer

Jean Kay. A retrospective reading of Linear Manuel, aqnb

2013

Elvia Wilk. Gordian Conviviality, Frieze d/e Issue #10, June August

Pablo Larios. Meet Berlin-based artist Juliette Bonneviot, Kaleidoscope blog

2012

Coline Milliard. Digital Gets Physical at Dublin’s Temple Bar Gallery, Blouin Artinfo

Amy Knight. Juliette Bonneviot, Symbol, Paper For New Art, Issue #2, Summer

Orit Gat. Artist Profile: Juliette Bonneviot, Rhizome

Natalie Esteve. Follow ‘Les Urbaines’, Kaleidoscope blog

2011

Karen Archey. Nett ist die kleiner Schwester von Scheiße, Rhizome

Jens Hinrichsen. Warum immer woanders?, Monopol

Awards

2016

Ars Viva 2016, nominee

Curation

2010

Etat de choses, co-curating with Aude Pariset, Darsa Comfort, Zurich

Enchanted, School of Development, Berlin